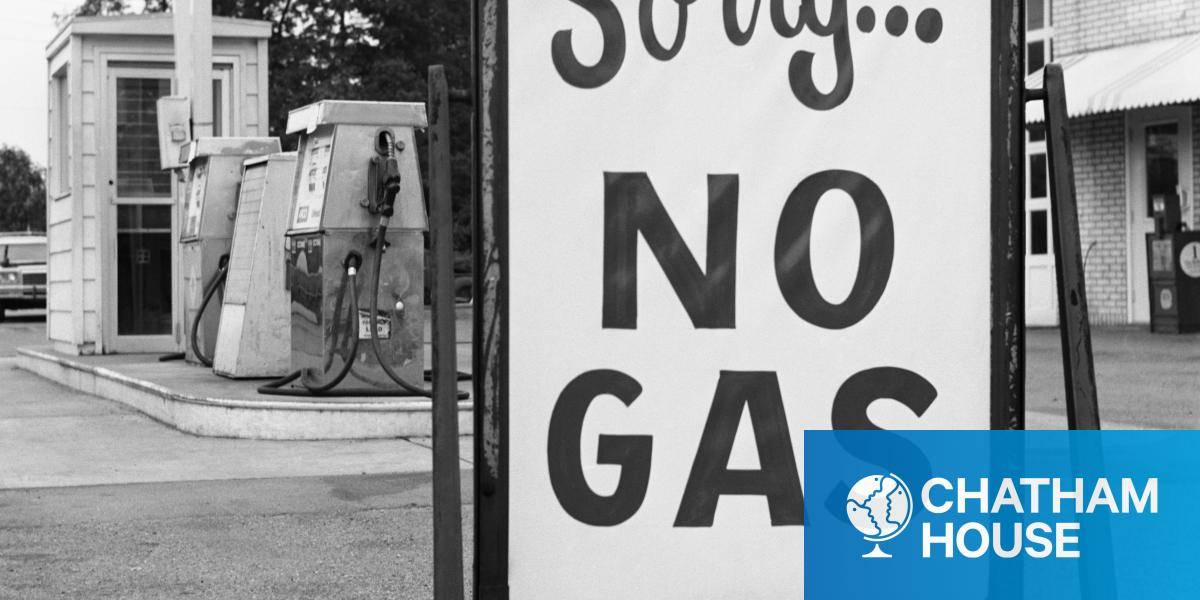

Date with history: How the oil crisis changed the world

The World Today

mhiggins.drupal

26 September 2023

After Opec cut oil production on October 17, 1973, millions were displaced from Afghanistan and Syria, transforming global politics, argues Randall Hansen.

Fifty years ago, the biggest oil producers in the Middle East asserted their power with a momentous embargo. The ensuing oil crisis had many consequences, one of which was ultimately to displace tens of millions of people in the region, changing geopolitics up to this day.

In October 1973, Arab members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (Opec), led by King Faisal of Saudi Arabia, announced an embargo on oil sales to America, Britain, Canada, Japan and the Netherlands in retaliation for their support of Israel in the Yom Kippur war that was briefly fought that month.

On October 17, Opec announced rolling monthly 5 per cent reductions in oil production, halving it within six months. The result was a quadrupling of prices within a year and the first oil crisis. The embargo lasted six months; the oil price rise lasted a decade. But the effects on global migration, economics and politics are still with us.

Today, there are more forced migrants than at any time in history: 110 million. The majority – 62.5 million – are internally displaced. More than 35 million are refugees who have fled war, violence or persecution and have crossed an international border to find safety. Another five million are seeking asylum.

Four of the five countries hosting the greatest number of refugees are in the global south – Turkey, Iran, Colombia and Pakistan. The other is Germany. Some 6.8 million refugees come from Syria, and 5.7 million from both Ukraine and Afghanistan.

Migration on a massive scale

In all three cases, the refugees fled war. In the case of Ukraine, the cause was immediate and direct – Putin’s decision to launch an illegal attack on Ukraine in February 2022. In the cases of Afghanistan’s and Syria’s refugees, many factors intervened. But though no direct line can be traced back to the events of 1973, the Opec oil crisis was a necessary precondition of their flight.

The embargo and oil price surge transformed geopolitics. Oil money flooded the oil-rich Gulf States – Saudi Arabia above all, but also the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Iran and Iraq – underpinning large infrastructure projects requiring the migration of labour on a huge scale.

For the oil-poor Middle Eastern states, such as Syria, the effects were devastating. Oil price-induced inflation ended the country’s already ailing attempt to industrialize behind a tariff wall. When growth collapsed and inflation surged in the 1980s, the country shifted to liberal capitalism: privatization, reduced subsidies, more open trade and inward US investment.

Wealth was generated, but it resulted in large-scale inequality. By 2010, some 30 per cent of Syrians were living below the poverty line, with fully 11 per cent below the subsistence level. There was also a chronic shortage of social housing.

Discontent burst out on to the streets in the Arab Spring. We think of the Arab Spring as a movement for democracy, but it was fundamentally a call for economic justice. When Mohamed Bouazizi, the Tunisian street vendor, set himself alight in December 2010, his last words were: ‘How do you expect me to earn a living?’

In public opinion surveys conducted by Arab Barometer between 2012 and 2014, ‘fighting corruption’ and ‘betterment of the economic situation’ were cited by 64 per cent and 63 per cent respectively as causes of the Arab Spring; civil and political freedoms by only 42 per cent.

These feelings were particularly acute in Syria. Street protests in the spring of 2011 led to a brutal crackdown and a civil war that generated almost seven million refugees, making Syria the largest refugee-producing country in the world, surpassing Afghanistan in 2014.

Afghan refugees were themselves in part the consequence of changes unleashed by Opec. For decades, Moscow had stolen Afghan gas. A late-1970s rural rebellion against the Soviets’ puppet regime in Kabul threatened to end that practice.

While securing their access to pilfered natural gas motivated the Soviets’ invasion in 1979, the oil price spiral that year – the second oil shock of the 1970s – convinced a previously hesitant Moscow that oil and gas resources would be there to pay for the invasion. As in Ukraine 43 years later, Moscow thought it would achieve a quick victory, installing a pliant regime in Kabul that would guarantee its access to pilfered natural resources.

It did not turn out that way. Declaring jihad, Afghan resisters in the countryside fought back with a tenacity and brutality that shocked Moscow. The Red Army responded by drenching the countryside in bullets, bombs and mines.

NBC news report from October, 1973, on the Opec oil embargo. Video: Retro Man / YouTube